Categories > Guides and Tips

Do people from Hong Kong prefer to identify as Chinese, British, or Hong Kongers?

- Do people in Hong Kong identify as British, Chinese, or Hong Konger?

- What causes Hong Kong residents to identify as Hong Kongers?

- Hong Kong’s Historical Background

- Hong Kong’s Cultural and Economic Differences with China

- Hong Kong’s Unstable Political Relationship with the Mainland

- Which age demographic prefers to identify as Hong Konger?

- Are there any other explanations for the national identity of Hong Kong residents?

The residents of Hong Kong have a unique history. They were once a British colony, and then were handed back to China but operated separately and distinctly from the mainland.

As such, many locals have differing views on how to identify themselves. Continue reading to know if the people of Hong Kong prefer to identify as Chinese, British, or Hong Konger.

Do people in Hong Kong identify as British, Chinese, or Hong Konger?

A majority of people in Hong Kong identify as Hong Konger instead of British or Chinese. In a survey by the University of Hong Kong, 53% of the 1,015 respondents identified as Hong Kongers while only 11% claimed to be Chinese.

Another survey by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute found that 39% of their 1000 respondents identified as Hong Konger, with 18% identifying as Chinese.

Out of the numerous polls conducted, none identified as British. However, it may be essential to know that the option to be called British is not an option in most surveys conducted in the first place.

What causes Hong Kong residents to identify as Hong Kongers?

Hong Kong residents likely identify as Hong Kongers due to their history, cultural and economic difference, and political relationship with China.

Even though Hong Kong is a special administrative region of China, Hong Kongers see themselves as separate and distinct people.

Let us discuss these in greater detail.

Hong Kong’s Historical Background

Compared to the rest of China, Hong Kong has a different historical background due to the region being leased to the British Empire back in 1898.

While the mainland was experiencing the rule of empires and dynasties from China, Hong Kong experienced a more Western type of culture that melded in with the region’s roots in the Han dynasty.

As a British colony, Hong Kong became a commercial gateway and distribution centre and served as an international trading hub for the East and West.

After 99 years, Britain turned over Hong Kong to China in 1997, with the latter putting the region under the one country, two systems policy. The residents of Hong Kong, however, were not part of the discussion and handover.

However, a study conducted by the Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs in 1983 found that 41.8% preferred to maintain the status quo at the time.

Many of these people said they didn’t want their lifestyles to change and that this was the only way to maintain the prosperity and stability of the territory.

According to the same study, 24.3% opted for self-administration under Chinese sovereignty, saying that Hong Kongers were more familiar with Hong Kong, but China owns the territory.

Also, 17.4% wanted Britain’s administration under Chinese sovereignty, and 7.4% preferred independence. The remaining 4.8% wanted Chinese administration and sovereignty.

With this research, one can infer how distinct Hong Kongers viewed themselves from the mainland ever since and how they wanted things to remain the same.

Hong Kong’s Cultural and Economic Differences with China

Due to Hong Kong’s history, the region underwent a different cultural trajectory. Since Hong Kong was an important trading hub, the region experienced foreign influence as people from different countries sought to trade with merchants in the area.

When China leased Hong Kong to Britain, the region experienced Westernization. Schools under the British Empire’s rule taught British ideals and philosophy and promoted Christianity and involvement in politics.

This Westernization is the reason why Hong Kongers speak English alongside Cantonese, even though most locals are afraid of speaking English.

Many advocates sprung up in this era, with some wanting the mainland to modernize and follow a more democratic path of government.

After going through a period of Western influence, Hong Kong returned to the sovereignty of China under the concept of “one country, two systems.”

Under the doctrine of “one country, two systems,” the mainland will not touch Hong Kong when it comes to the special administrative region’s government and economy.

This semi-autonomy is put in place because the SAR and mainland China have differing and nearly opposing systems in place.

Hong Kong operates primarily in a free-market capitalist service economy, with lower taxes, no tariffs, and a different currency compared to mainland China’s socialist market economy.

Hong Kong also holds democratic elections to choose its Chief Executive, while mainland China has a different method of putting leaders in place.

These economic differences, combined with Hong Kong’s colonial history, led to a way of life entirely distinct from the mainland. The region also got rich and drew in the wealthy from all over the world, further reinforcing the separation.

Hong Kong’s Unstable Political Relationship with the Mainland

Perhaps the most crucial thing that causes Hong Kong residents to identify as Hong Konger instead of Chinese is their desire to separate from mainland China’s politics and government.

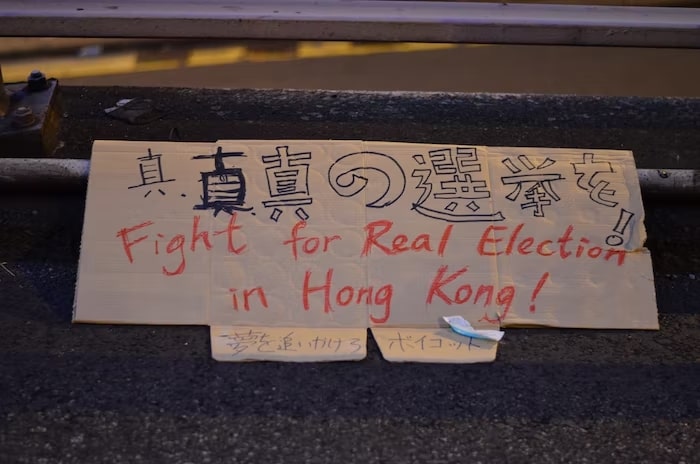

Many Hong Kongers have been protesting Beijing’s policies ever since the handover in the late 1990s. Many Hong Kong residents are pushing back against laws that they believe would stifle their freedoms and increase mainland China’s control over the region.

Pro-democracy demonstrations and protests led by students have been intensifying over the years, as numerous youth advocate for democratic elections and reject the increasing Beijing influence over the region.

These protests reached a tipping point in 2019 when activists flooded the streets in opposition to a bill that would allow the extradition of suspected criminals to Beijing.

These movements led up to the introduction of the National Security Law that spurred even more unrest and unhappiness.

In interviews with the New York Times, Hong Kongers have said that they don’t reject their identities as Chinese because they’ve never felt as such in the first place. Another resident said, “We don’t want to associate ourselves with Communist China.”

As the region is split between differing ideologies, those with pro-democracy sentiments further insist on their identity as Hong Kongers separate from China.

Which age demographic prefers to identify as Hong Konger?

| Age Demographic of Hong Kong Residents Identifying as Hong Konger | Percentage in Age Demographic |

| 18 – 29 years old | 76% |

| 30 – 49 years old | 40% |

| 50+ years old | 29% |

Many studies show that out of all age groups, the youth tend to identify as Hong Konger more than those above 30 years old. According to a study by the Public Opinion Research Institute, 76% of respondents aged 18 – 29 years old identify as Hong Konger.

The inverse is true when it comes to Hong Kong people identifying as Chinese.

| Age Demographic of Hong Kong Residents Identifying as Chinese | Percentage in Age Demographic |

| 18 – 29 years old | 2% |

| 30 – 49 years old | 17% |

| 50+ years old | 23% |

Note: The options for this specific survey include Hong Konger, Hong Konger in China, Chinese, and Chinese in Hong Kong, which is why the tallies do not add up to 100%.

Some professionals, such as Wong Tsz Yuen, say that the reason why more elderly people identify as Chinese is that they were originally immigrants from the mainland. As such, their identity as Chinese citizens has stuck with them.

However, those born in Hong Kong identify more as Hong Konger because they were raised and grew up in the region.

Are there any other explanations for the national identity of Hong Kong residents?

Experts and analysts primarily attribute the identification of locals as Hong Kongers to emigration, the youth’s political identity and biases, and unprofessional survey questions.

For example, a possible explanation for the results that a majority of residents identify as Hong Kongers is that Hong Konger and Chinese are not mutually exclusive or virtual opposites.

In an interview, Phoenix TV reporter Wong Tsz Yuen said that interviewees may choose the “Hong Konger” option but not necessarily disagree with being classified as “Chinese,” as the questions are too broad and not rigorous enough.

Wong Tsz Yuen also blames the strong preference of the youth towards identifying as Hong Konger on their “outsider’s view of China,” which they say degenerates into an “us-against-them” attitude towards the mainland.

Some analysts also attribute the increase in people identifying as “Chinese” to the recent wave of emigration.

As Hong Kongers continue to leave the region in fear of prosecution and to avoid the government’s strict policies, those with pro-Beijing sentiments have a higher chance of getting polled.